SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH

|

Scientific Research underscores everything that we do at CCB, from fact-finding and new discoveries, to the monitoring and evaluation we do on our own projects. It is a part of everything we do and the results from this work helps steer us towards more practical and innovative ways in which to protect cheetahs and help communities in Botswana.

All of our research centres around human-wildlife conflict and all of our research projects have a strong conservation element to them. We focus solely on practical and useful research studies that we know will help us to mitigate human-wildlife conflict and protect cheetahs. Much research has been conducted in protected areas where wildlife roams free and without persecution, however research on the farmlands where the real threat to their survival exists, is less understood. By understanding the ways in which these populations are behaving we can unlock the potential solutions for human-wildlife conflict. By finding out how cheetahs are hunting we can find solutions for farmers by helping them to protect their livestock from predation, leading to fewer cheetahs being killed by farmers. Current ProjectsCheetah Population Dynamics

For threatened species, it is essential to understand the population trends over time to determine whether conservation programs are achieving their goals. Cheetahs have been monitored for many years in the commercial farms of western Botswana, an area experiencing the highest conflict for this species in the country. Monitoring studies have been conducted using a variety of techniques like spoor surveys and motion-activated camera trap surveys and we are now collating this information to assess whether cheetah numbers in the area have remained stable, increased or decreased over the past seven years. The information will help highlight whether cheetah’s area able to coexist with farmers in this environment, or if persecution is still the primary threat in this area. Biodiversity in Non-protected Areas

The importance of non-protected areas as wildlife habitats is often underestimated. Many species still survive and coexist in farming landscapes and knowing what species are present and what influences their distribution and occupancy is vital for farmers to be able to manage the wildlife/livestock interface on their farms. CCB has been using motion-activated cameras to assess biodiversity on commercial farmlands in the Ghanzi District. These studies have also extended to nearby wildlife management areas and can be compared with results from protected areas throughout the country. Knowledge of biodiversity in various land use types is essential for conservation efforts at the national level. So far we have found that a surprising number of species are able to coexist alongside livestock, with several species not previously documented for the area being found by our cameras. Finding Conflict Solutions

As human-wildlife conflict continues to be a problem in many areas across the globe, it is essential to find practical and effective solutions to reduce both livestock loss and carnivore persecution. CCB has trialled a number of mitigation projects aimed at reducing conflict. A number of projects have involved the use of deterrents — devices aimed at deterring carnivores from an area, particularly at key locations like kraals or waterpoints that are utilised by livestock, in order to reduce predation. Trials involving Foxlights have shown some limited success in the farmlands, and the research team is now embarking on new trials of Skaapwagters (devices equipped with light, sound and scent deterrents to ward off carnivore species), used successfully in South Africa, to see if they can also deter carnivores from high conflict areas. We have also deployed tracking collars on cattle to see if patterns of livestock movements can help equip us with knowledge to develop management methods than can also reduce depredation, such as kraaling vulnerable stock or utilising rotational grazing. Livestock Guarding Dog Assessment

We conduct monitoring and evaluation of our Livestock Guarding Dog (LGD) programme — a programme where we train and place LGDs with farmers experiencing conflict with cheetahs. Regular monitoring of the dogs and the farms where they are placed allows our research team together with our “Farming for Conservation” team, to assess the progress of the dogs and analyse whether the placement program is effective. The results of this analysis (data is still being collected at present) will be compared to results found from our research conducted on LGDs sourced by farmers themselves, which was conducted Botswana-wide between 2010-2015 (see below). Collaring of Cheetah

The use of VHF and GPS collars is a very popular method for many wildlife studies. Collars can provide information on home range size, habitat selection, fine scale movements and even hunting strategies for species that are hard to track on foot or by vehicle. CCB has utilised collars for many years in the Kalahari region of Botswana for a range of studies. New studies involving the use of collars are aimed at determining movements of cheetah in other non-protected areas, such as communal farming areas and wildlife management areas. By showing farmers how vast cheetahs home ranges are we help them to understand that cheetahs they see on their farms are not staying in one spot, but utilise large areas to survive. This can often help alleviate some of the threat that farmers feel from carnivores that they live alongside of. Coexistence in Wildlife Corridors

Maintaining effective corridors for wildlife between protected areas is a challenge, as communities and people reside in these areas, which often escalates conflict situations between people and wildlife. A key area in Botswana that facilitates movement of many wildlife species including cheetah, is known as the Western Kalahari Conservation Corridor (WKCC). This corridor is crucial in linking the south-western population of cheetahs (the largest in the country) with the central and northern populations. CCB has highlighted this area as a focal point to work with communities residing here in an effort to help encourage coexistence and provide a supporting framework for other pressing issues. CCB’s Scientific Research department is undertaking questionnaire studies to understand many of the issues facing these communities, primarily as a result of conflict resulting in livestock loss and retaliation killings of carnivores. This will help us understand the present situation, threats and challenges, which can assist in determining the right solutions to address these issues. Spoor Surveys

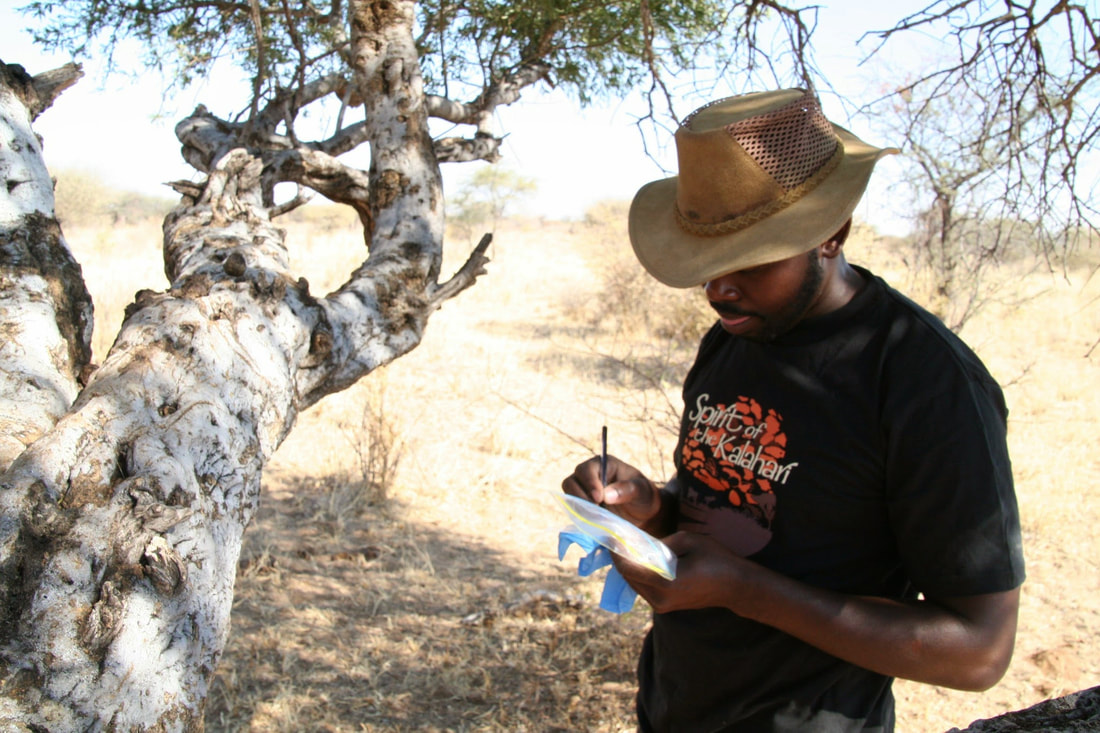

CCB is utilising the expert skills of the Kalahari San Bushman trackers in monitoring carnivore populations in the Ghanzi District. Bushman trackers have been used by the research team to find cheetah marking trees — hotspot locations that are heavily utilised particularly by male cheetahs and are great places for monitoring cheetah in any given area. Additionally, the research department have used trackers for spoor surveys to assess density for several carnivore species across the farmlands and in determining potential transboundary movements between Botswana and Namibia. Previous ProjectsPilot Study with a Local Tswana Scat Detection Dog

In wildlife studies, specific breeds of dogs that are trained to detect scat (poop) of threatened species, are known as “scat dogs”. This technique is becoming widely popular, particularly for species that exist in low populations or low densities, such as the cheetah. However, not all breeds of dogs are suitable for the hot arid climates where cheetah are commonly found. The Kalahari is a harsh place and imported breeds of scat detection dogs have struggled to work in the heat that they encounter here. Training of a locally bred dog is currently underway at CCB to determine their effectiveness in locating cheetah scat. Local mixed-breed dogs, commonly known as “Tswana dogs” are well adapted to the local climate and terrain and are incredibly hardy due to a history of strong natural selection. We are the first organisation in southern Africa to promote the use of locally adapted dogs to detect scat and preliminary results show that “Loeto” — our first Tswana scat dog — is doing very well. Having locally-sourced scat dogs would be highly beneficial in improving studies of populations and behaviour, particularly in non-protected areas where this species deserves crucial conservation efforts. We are very excited about the chance to show the world that local dogs are not only capable but are high effective when used for this purpose. Cheetah Marking Tree Lures

Locating cheetahs in large farming areas can be extremely difficult, due to their wide-ranging behaviour, avoidance of people and low population numbers. Cheetahs, particularly males, however do commonly visit cheetah “marking trees” which are communal scent-marking sites. To improve the chances of locating cheetahs, trials have been used to determine whether the use of lures can be used to create artificial marking trees. If successful, lures could drastically improve opportunities to collar and/or monitor cheetahs using camera traps. This ultimately will enhance research efforts in increasing information in areas where cheetah conservation is of priority. Cheetah Diet Analysis

By analyzing hairs found in the scat (poop) of cheetahs, we can distinguish what they have been eating. The diet analysis that we conducted from scats found at the cheetah marking trees is incredibly useful. By looking at the cheetah diets we can know which wild species of game to conserve to encourage cheetah survival on livestock farms while minimizing predation on livestock. Diet research is also valuable in demonstrating to farmers that not every cheetah is a livestock killer. After many hundreds of scat samples, CCB’s research team has found that the proportion of livestock in these cheetahs’ diets was below 6% and that they actively chose to predate on their natural prey even when livestock was present. National Geographic’s Crittercam Project

In May 2012, CCB teamed up with National Geographic to utilise new technology using video collars called “Crittercams”. The Crittercam allows us to look directly into the lives of wild cheetahs from a cheetahs-eye perspective for the first time in history to see what their daily lives entail. The Cheetah Crittercam project has given a new insight into cheetah behaviour in heavily bush encroached farmlands, using this ground-breaking technology. Four cheetahs were fitted with the Crittercam units mounted on specially designed collars. Footage retrieved from the drop-off collars have shown us how cheetahs have to search for surface water in the dry Kalahari and showed them feeding on free ranging kudu, their top choice of prey in that area. Nation-wide Survey of Livestock Guarding Dogs

Between 2010 and 2015 our research team conducted the first ever study into the use of livestock guarding dogs (LGDs) as a human-wildlife conflict mitigation tool in Botswana. It was also the first study in the region to assess the effectiveness of various breeds of dog as LGDs. Not only did the study show that LGDs were incredibly effective, reducing depredation events by, on average, 75%, but the study also helped shape new training techniques for LGDs that we are now using at our LGD training centre. The study also revealed the success of local mixed breed dogs known locally as Tswana dogs. Tswana dogs were shown to be the most affordable breed for farmers to employ and performed well across all aspects of guarding, showing low levels of behavioural problems and minimal health problems and causing large reductions in livestock loss. We hope that this study gives Tswana dogs the reputation they deserve as hard-working, hardy, cost-effective and brave livestock guardians. Translocations as a Tool to Mitigate Conflict

Translocations are the process of removing “problem animals” from areas where they are causing conflicts and relocating them to other areas. This technique is one of the primary tools used by the Department of Wildlife and National Parks and some NGOs in the region to deal with human-wildlife conflict, however, it’s effectiveness had not been tested. A study conducted by CCB between 2010 and 2013 saw to collaring all cheetahs that were translocated due to conflict to assess their survival rates and whether or not they returned to the areas that they were removed from. This study revealed that only 18% of the cheetahs translocated were still alive a year after they were moved and some of these animals did return to where they were caught. Analysis of the conflict situations on the ground revealed that although removing the “problem animals” did in some cases reduce livestock depredations temporarily, the effects were only short-lived. In most cases the farmers continued to have problems with carnivores even after translocations occurred. These results help us to emphasize our stance that prevention is always better than a cure, and that human-wildlife conflicts are best addressed by increasing the protection of livestock so that they are less vulnerable to predation. This study has also shaped our own policies and we no longer conduct translocations unless numerous preventative strategies are in place and all possible non-lethal deterrents have been used to try to mitigate the conflict taking place. |